It was a January night like any other for Hernan Humana as a new decade dawned in Chile. Which meant it was a night when he knew what the ringing phone might foretell.

“Hernan, I think your time has come.”

The words on the other end of the line that night weren’t meant as a threat. But in Chile in 1980, they chilled Humana to the bone.

The friend on the phone, a doctor, had been at a Chilean Olympic Committee meeting. A man in military uniform had opened his briefcase and taken out a Canadian newspaper critical of Augusto Pinochet, the dictator who seized power in a 1973 coup. Humana’s father, who fled Chile several years before, was the newspaper’s publisher. The military officer suggested that instead of praising Humana, a Chilean volleyball international and a coach in the youth national system, someone should cut his throat.

“When a military man in Chile at the time said that, it’s not a figure of speech,” Humana recalled. “It’s a threat. In less than two weeks, I was out of the country. That’s how I left Chile.”

These days a professor in York University’s School of Kinesiology and Health Sciences, he arrived in Canada four decades ago with few marketable skills beyond the volleyball court and no command of English. But in Chile at that time, you didn’t ignore warnings. Leaving was better than disappearing.

His daughter, Melissa Humana-Paredes, was born a little more than a decade after he arrived in Toronto. She knew little growing up about the dark years her parents lived under a dictatorship. She heard nothing about the inner turmoil her father felt when he represented Chile in international competition. Instead, she learned to share her father’s passion for a sport that ultimately shaped both their lives. Along with partner Sarah Pavan, she is a reigning beach volleyball world champion and among the gold medal favorite in the Olympics.

Love grows back stronger after heartbreak. Joy means more after sorrow. One of beach volleyball’s best players and most ebullient souls, joy for life and sport may lead Humana-Paredes, 28, to Olympic gold in Tokyo. They were also all her father took with him when he fled Pinochet’s Chile at 27.

“I was the same age as them when they were going through the coup and dictatorship,” Humana-Paredes said. “To put myself in those shoes, I can’t fathom it. I can’t relate to everything they went through at my age. And they came through and persevered and came to a new country and created a new life. My parents are just the happiest people and have this zest for life. You would never know that in their past they saw such horrors and atrocities.

“It made me look at them in a different light. You understand them differently.”

Volleyball under a dictator

Humana had already played for the Chilean national team by the time a coup changed everything about life in the country, including what the flag represented. He was a university student in Santiago on Sept. 11, 1973, when Augusto Pinochet’s military junta seized power from the democratically-elected government of President Salvador Allende. He saw confusion in the streets as people began to learn what was happening. Living in housing for national team athletes, he spent Septermber 12 under curfew and visited by soldiers. He was finally able to venture outside again on September 13.

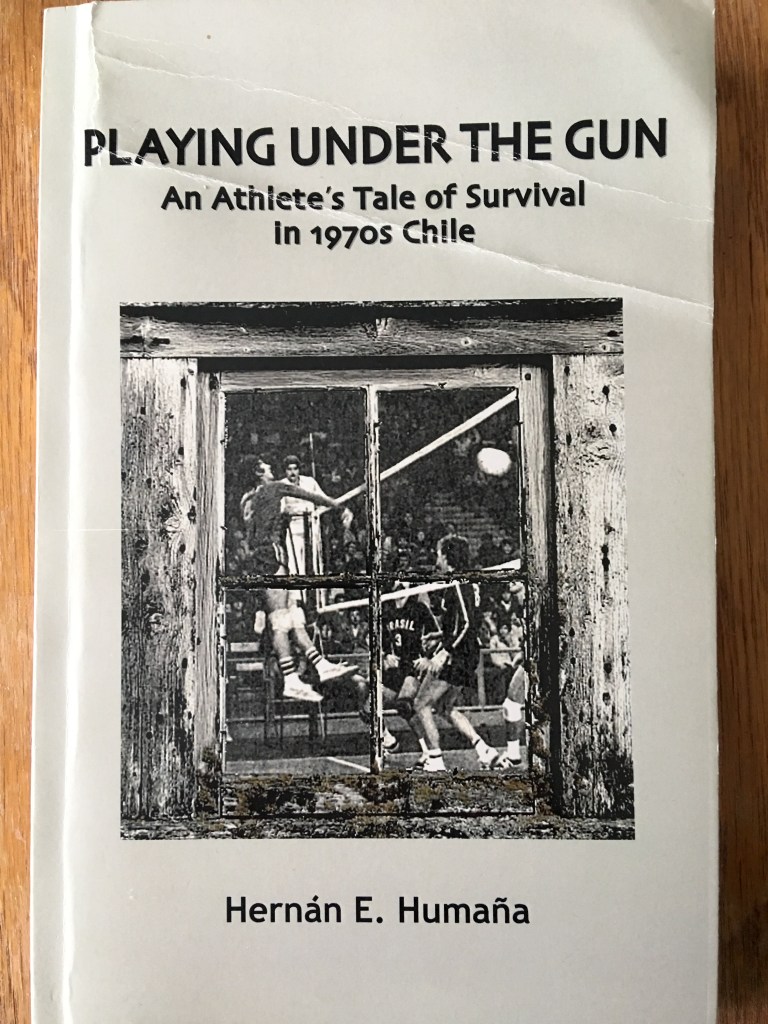

In Playing Under the Gun: An Athlete’s Tale of Survival in 1970s Chile, his memoir, he recounts a conversation with a neighbor limping down the street.

He spoke slowly, as if seeing life around him in some terrible new light. On September 11, he was arrested by a military patrol and taken to the national stadium, where he was tortured. His interrogators wanted to know who was organizing the resistance in his neighborhood. He was burned with cigarettes butts, and electric cattle prods were applied all over his body. He raised his shirt to reveal purple bruises and burns all over his skin. It was shocking. I didn’t know what to say. How could I communicate my compassion for him? Nobody is taught proper etiquette for dealing with victims of torture.

The neighbor’s experience was one endured by far too many Chileans in the months and years that followed the coup, tens of thousands of ordinary citizens who were arrested, tortured, murdered or simply disappeared, their fates unconfirmed but also obvious.

Humana’s experience under the dictatorship was more fortunate by comparison, but it was also emblematic of the fugue that fell over the country. He had close calls. Soldiers searched his dorm room but didn’t notice proscribed books. A friend told him he had been denounced by a neighbor as an Allende sympathizer and militant. He was suspended from university for two years after running afoul of authorities. His father was arrested and detained for months, then blacklisted from any jobs in his former field of engineering. But like the vast swath of Chileans who were neither Pinochet supporters nor suffered the harshest fate in makeshift prisons, Humana mostly tried to find some normal routine in a country he hardly recognized.

In a chapter titled “Playing with Ghosts,” Humana writes about so often playing volleyball in what was then called the Estadio Chile, the national arena in Santiago. Along with the Estadio Nacional, the outdoor soccer stadium, it became a concentration camp and place of torture and execution following the coup (it was subsequently renamed in honor of Victor Jara, the poet who was tortured and murdered by Pinochet’s forces in the regime’s earliest days).

On one occasion, when he was playing particularly poorly, a friend cajoled him to do better for those who died there.

I remember looking straight into his eyes and silently wondering how he couldn’t understand what I was feeling. This was just a meaningless volleyball game. The real issue was the horrors so many had endured in this place. I did not say anything, and my game didn’t change drastically. I think that I had reached some kind of critical point. Perhaps I was more vulnerable that day, overcome by a profound sense of hopelessness for my country. All I know is that I didn’t want to play that day. Or better put, I couldn’t play that day.

Almost from the moment Pinochet seized power, when his volleyball team was dragooned into a farce of a youth festival at the national stadium, Humana and other athletes faced a dilemma familiar to those living under repressive regimes. Play on and offer what silent or subtle protest they could? Or refuse, risking the safety of friends and family and leaving spaces that would be filled by toadies all too willing to praise Pinochet and belt out the national anthem?

And when I didn’t play well, perhaps it was because I was on some level confronting the horrors, and confronting my own complicity through my role as the symbolic representative of the perpetrators.

His parents and siblings finally left for Canada in 1975. He remained in Chile to finish university, delayed by the suspension and the loss of purposeful destruction of records under the new regime. He continued to play the sport he loved. Although even that was forever changed.

By then, the beachfront club Trauco was long gone. Located in the city of Quintero, on the Pacific Ocean northwest of Santiago, Trauco was the spot where Humana fell in love with beach volleyball. He spent summers there at the invitation of the club owner, nominally working in the evenings but mostly playing for the club’s beach volleyball team. The club and volleyball carried on for a couple of years after the coup, but then Pinochet’s soldiers showed up one summer and destroyed all of it.

The Chile in which such things thrived was a fading, bitter memory.

A new life in Canada

So when the warning phone call finally came in 1980, the friend’s account of the Olympic Committee meeting quickly confirmed by another present, it was hardly a surprise. He made it through more than six years, but no one who wasn’t subservient could make it forever. There wasn’t any midnight run for the border, but within a week or two, he was in Canada.

His younger brother helped Humana make inroads in the volleyball community — and helped translate initially. Humana received an advanced coach certificate from York in 1983 and his Master’s from the school in 1993. He coached both men’s and women’s volleyball for York at various times.

In 1995, John Child approached Humana, his former youth indoor coach, about coaching beach volleyball. After appearing as a demonstration sport in the 1992 Olympics, beach volleyball was added to the regular program for the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. Calling on his experience in the sand in Chile, Humana took on the new challenge. Child and partner Mark Heese went on to win the bronze medal.

That remains Canada’s only Olympic medal in men’s or women’s beach volleyball. But that may be on the verge of changing. Humana-Paredes was still a few months shy of her fourth birthday in 1996, but she spent a lot of time in the sand while her dad continued to coach indoors and outdoors following the Olympics. Yet Humana recalls that far from him dragging her to practice, it was more often Melissa knocking on his door early on Saturday mornings to go and play.

“By no means was it pushed on us by our dad,” Humana-Paredes concurred. “He exposed us to the sport, and it was always around because we would be at the beaches to watch him practice and whatnot, but he never forced us into anything.

“For me, it was an immediate attraction. I started playing as soon as I could.”

Melissa Humana-Paredes goes for gold

While the picture may be changing with the growth of beach volleyball as an NCAA sport, notably including current Latvian Olympian Tina Graudina and former UCLA standouts and Canadian twins Megan and Nicole McNamara, it was still unusual 10-to-15 years ago for a teenager like Humana-Paredes to train almost exclusively for beach volleyball.

“She was by herself the whole winter playing beach volleyball alone,” Humana said. “It was a lonely, lonely battle. I was there with her, but it was a lonely battle. She would miss indoor, the social aspect and the friends that you make. She’s a very social person. But she loves beach volleyball. That’s her sport.”

She ultimately played four successful indoor seasons for York, where Hernan had previously coached the women’s volleyball team. But even then, the beach was her focus. After her freshman year at York, she and partner Taylor Pischke won a silver medal at the 2011 FIVB Junior World Championship in Halifax, losing to Switzerland’s Nina Betschart and Joanna Heidrich in the the final match (a decade later, three of the four are in the Olympics).

“I love beach because the incredible mental, physical and emotional challenges that it brings,” Humana-Paredes said. “You’re more involved in the game, you have more control of the game — you’re more independent.”

She played her first major pro event while still in college. A few months after finishing at York, she and Pischke reached the quarterfinals of a full-fledged FIVB event in Sao Paolo.

But it was while serving as a training player for the Canadian teams that qualified for the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro that she got to know Pavan, the former NCAA indoor All-American at Nebraska. A few months later, back in Rio, they finished second in their first FIVB tournament together. They won a five-star event later that summer and soared up the rankings, Pavan’s prowess at the net a perfect complement to Humana-Paredes’ defense and passing.

In 2019, they won the World Championship in Hamburg, Germany, beating April Ross and Alix Klineman in the final and losing just two sets in five knockout round matches. That win came with the added bonus of automatic Olympic qualification, which proved all the more valuable as most other teams scrambled to adjust the pandemic-dictated qualification process this year.

Hernan coached her in the early years. He certainly had the resume for it, from the Olympic success in 1996 to running a beach volleyball club in Ontario. But he said that both agreed when she was a teenager that it would be better for her to work with the coaches then in the Canadian national program. Besides, the professional circuit that takes her from Asia to Europe to South America on a near-weekly basis wouldn’t fit a university professor’s life very well.

Still, when the frequently California-based Humana-Paredes returns to Toronto, it is her father serving her ball after ball in the otherwise empty gym. Just like always.

“My dad will always be my coach,” Humana-Paredes said of his influence nonetheless. “With his knowledge and background and passion and love for the game, I always respect and care for everything he tells me — whether I agree with it or not. I’ll always take what he says to heart.”

All the more after his memoir, which Humana dedicated to Melissa and her brother Felipe, and shared with them while writing it. Although they visited Chile on multiple occasions growing up, Pinochet finally ousted in 1988, they knew few of the details of their father’s life in Chile.

It is a story about the resiliency of joy. The same joy evident when Humana-Paredes plays. The joy she will feel listening to the Canadian anthem if she and Pavan stand atop the podium. It will sound far sweeter than the Chilean anthem did to her father by the end.

Maybe too much happened to too many to speak of winners and losers. But joy survived.