Did I come to Maastricht for a bookstore? It depends on our starting point.

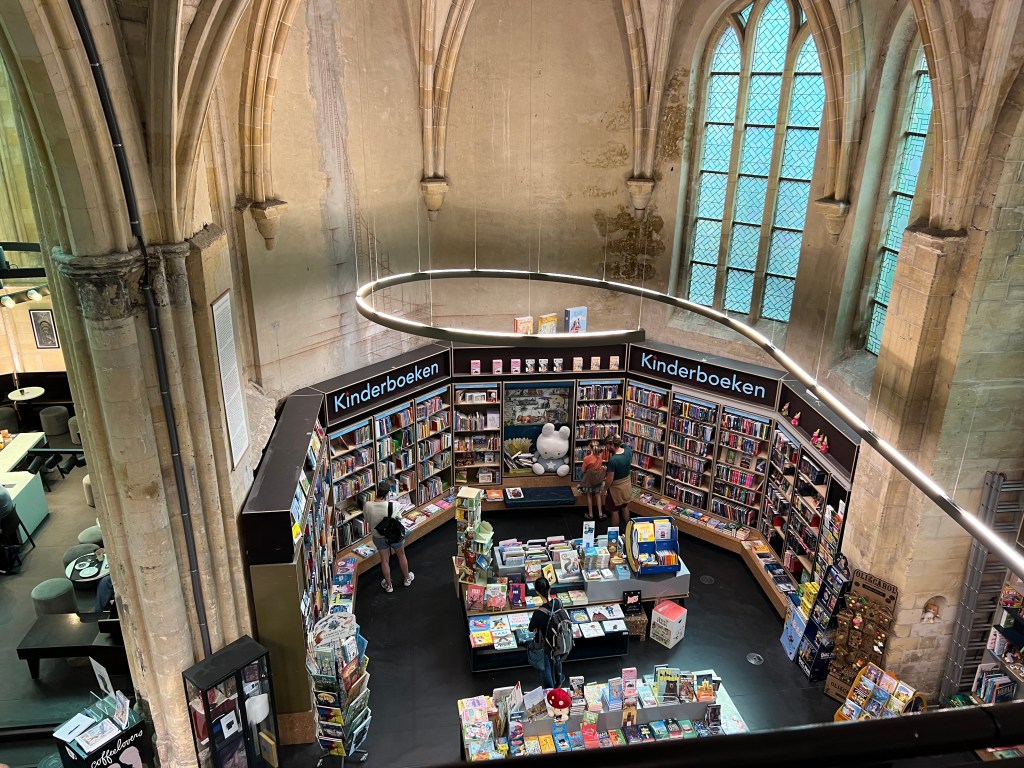

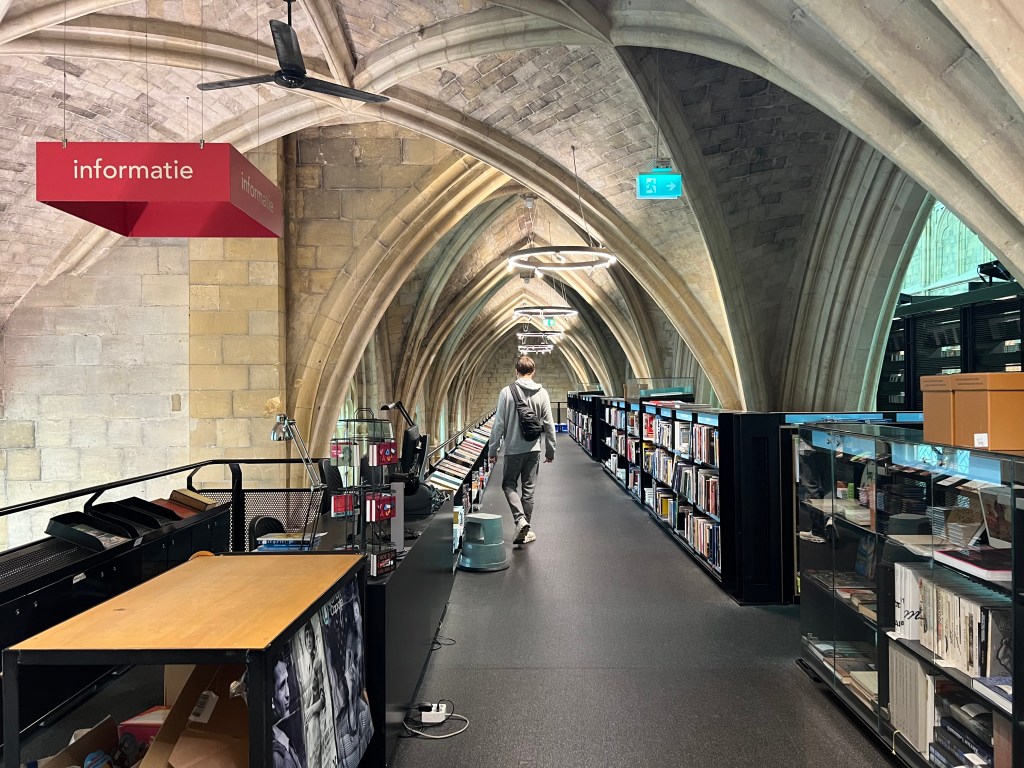

No, I didn’t trek all the way to Europe to visit the Boekhandel Dominicanen, which is inside a church originally constructed in 1294, more than a century before Johannes Gutenberg invented his moveable-type printing press to make that future possible. But I’m not sure I would have added Maastricht to my itinerary if not for its one-of-a-kind bookstore (it hasn’t been a functioning church since the French Revolutionary Wars spilled over into the Low Countries and the French used it for horse stables).

The bookstore sealed the deal when, looking for an appealing place to spend a couple of days before moving on to Dusseldorf, I learned about it as a point of interest in the small geographically quirky city (in a spit of the Netherlands wedged between Belgium and Germany) that earned positive reviews for walkability, atmosphere, history and scant tourist hordes.

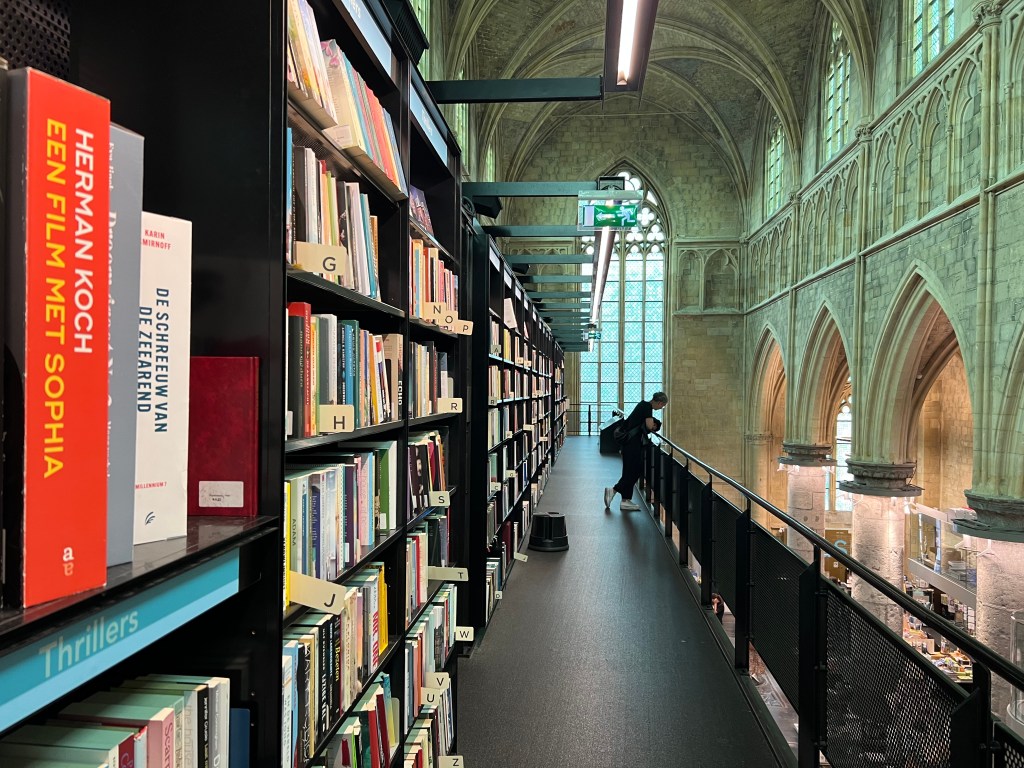

Now, as it turns out, the Bookstore Dominicanen is not an unforgettable bookstore for the purpose of finding books to read. This wasn’t all that surprising. I don’t think it would qualify as a great bookstore even if you read Dutch, which understandably appeared to account for about 75 percent of the inventory. Perhaps because most of its square footage is vertical, it doesn’t have a huge selection. It makes up for that lack of quantity in the quality of the selection, to a point. It’s decidedly less reliant on a handful of best-sellers than the typical airport bookstore, for instance. But it’s not a temple of deep cuts and staff picks. And because of the narrow aisles and people (like me) taking photos, even on a Monday morning, it is not super conducive to browsing.

But it’s a good enough traditional bookstore to come away happy from a once-in-a-lifetime bookstore experience.

Because the Bookstore Dominicanen isn’t really about finding something to read (I walked out with Gareth Rubin’s Holmes and Moriarity). It’s an endearing tribute band of a bookstore, a celebration of books—look where we can put a bookstore! Take your Index Librorum Prohibitorum and shove it, Pope Paul IV, here’s a fantasy novel about a kickass demon-keeping teenage witch. In that, it succeeds wildly. I walked away happy because it brought me back to all of the amazing (and, yes, better) bookstores in which I’ve gotten lost over the years.

When I lived in the Pacific Northwest, Powell’s in Portland and Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle. When I returned to visit over the years, Cloud and Leaf, the perfect vacation bookstore in the out-of-the-way beach town of Manzanita, Oregon—three blocks from the ocean, a tiny store somehow always full of books I wanted to read.

Or Powell’s secondhand bookstore near the University of Chicago, related through the eponymous family to the more famous Portland institution and always full of rare baseball titles when our family made summer trips to Chicago and games at Wrigley Field.

From an even younger age, so long ago that I don’t remember the names of the individual establishments, if I ever knew them at all, the bookstores in London and Cambridge that were full of Paddington, the Wind in the Willows, Frog and Toad and more.

The first Borders that opened in Indianapolis was a seemingly miraculous development in an area that was a bookstore desert. Long before it moved to a much larger superstore location with music, café and all the other accoutrements of its war with Barnes and Noble, it was just books. The nooks and crannies turned each section into its own principality, like some Holy Roman Empire of history, literature and more near one of our many, many malls.

Even abroad, I’ll wander into bookstores that, unlike the Dominicanen, don’t have any titles in English. The look and feel of the store is familiar. It’s still enjoyable to peruse a shelf.

I go to bookstores now and wince at the prices, contemplating what I need to cut out of the monthly budget to buy a couple of hardcovers. Yet somehow, to my parents’ everlasting credit, bookstores were places where we, as kids, didn’t need to beg or plead. Sure, they might draw a line when your tower of books grew too tall for you to carry, but they wielded the necessary accounting wizardry to make it work in their budget.

The rules of the real world never applied in bookstores, which in its own way, is at least as magical as anything you find through the back of a wardrobe.

In a bookstore, all the more before the internet, you could go anywhere and do anything. You could walk into a store and learn about people, placed and times you never knew existed until that moment. Try finding anything that revelatory at Bed, Bath and Beyond.

That’s what is special about the Bookstore Dominicanen. It’s celebrates the idea of bookstores—that here anything is possible. Even a bookstore in a church built before the printing press.